Oscar Vail is a technology expert whose work sits at the cutting edge of AI and cognitive science, exploring how machines can understand the very fabric of human experience. His team’s recent breakthrough—a computational model that learns to form emotion concepts—challenges the long-held belief that emotions are innate and pushes us closer to creating truly empathetic artificial intelligence. In our conversation, we delve into how this AI learns without pre-programmed labels by integrating sight, bodily signals, and language. We also discuss the surprising accuracy of its findings, its potential to revolutionize healthcare for non-verbal patients, the ethical considerations that come with such powerful technology, and what the future holds for emotion-aware AI.

Your computational model learned to categorize emotions by integrating bodily signals, sensory data, and language without pre-programmed labels. Could you walk us through how this works and what it suggests about emotions being constructed rather than innate? Please provide some specific details.

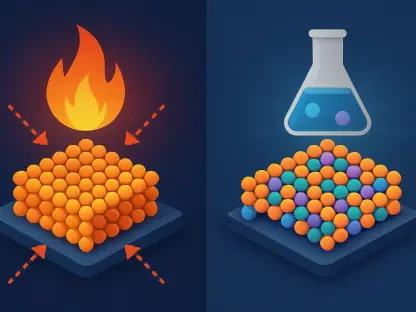

Absolutely. It’s a fascinating departure from the old way of thinking about emotions as these pre-packaged, universal reflexes. Our work is grounded in the theory of constructed emotion, which posits that our brain actively builds emotional experiences in the moment. To model this, we didn’t just feed an AI a dictionary of what “sadness” or “joy” looks like. Instead, we created a system—a multilayered multimodal latent Dirichlet allocation model, or mMLDA—and gave it the raw ingredients humans use: images that evoke feelings, the verbal descriptions people provided, and their raw physiological data, specifically their heart rate. The model’s job was to find the hidden statistical patterns, to see how a racing heart, the word “terrifying,” and the image of a snarling dog might cluster together. It essentially learned to form the concept of “fear” from scratch, which strongly supports the idea that emotions are complex concepts we construct, not simple reactions we’re born with.

Your model’s emotion concepts aligned with human self-reports with about 75% accuracy. What was the most surprising pattern the AI discovered in the data, and what does this level of accuracy imply for creating truly empathetic AI? Please share some insights from the testing phase.

Achieving that 75% agreement rate was a major validation, as it’s significantly higher than random chance. What truly struck me during the testing phase wasn’t a single, isolated pattern but the model’s ability to capture the nuance between closely related states. For example, it could begin to differentiate the physiological and linguistic signatures of high-arousal negative emotions, like fear, from low-arousal ones, like sadness, without ever being told those labels exist. It saw how the language and heart rate patterns diverged. This level of accuracy is a critical step toward genuine AI empathy. It suggests we can build systems that don’t just recognize a smile and label it “happy,” but can understand the underlying blend of sensory, bodily, and cognitive data that constitutes that happiness. It’s the difference between faking empathy and actually modeling its core components.

You’ve suggested this AI could help in healthcare, particularly for conditions like dementia where patients struggle to verbalize feelings. How might this technology function in a clinical setting to infer emotional states, and what are the primary ethical considerations we must address first?

The potential in healthcare is profound. Imagine a patient with advanced dementia who can no longer articulate their distress or contentment. A system based on our model could be integrated into a wearable sensor and a room’s ambient sensors. It would continuously and passively monitor heart rate, perhaps observe what the patient is looking at, and listen for non-verbal cues. By integrating these data streams, it could infer an emotional state—for instance, flagging a spike in distress when a particular caregiver enters the room or noting a state of calm when classical music is playing. This could provide invaluable feedback to caregivers. However, the ethical tightrope we must walk is incredibly fine. We are talking about inferring a person’s innermost state, so data privacy and consent are paramount. We must ensure the technology is used to enhance care, not for surveillance, and that there are always clear protocols for who can access this deeply personal information and how it can be used.

The model was trained using images, verbal descriptions, and heart rate data. How might incorporating other data types, such as facial expressions or vocal tone, change the model’s understanding of emotion, and what are the next steps for refining its accuracy and complexity?

That’s precisely where our research is headed next. The current model is a powerful proof of concept, but it’s only using a few pieces of the puzzle. The human emotional experience is incredibly rich with data. Adding vocal prosody—the pitch, rhythm, and tone of someone’s voice—would be a game-changer. Think of how much emotion is conveyed not by what we say, but how we say it. The same goes for micro-expressions and other subtle facial cues. Each new data stream we add will allow the model to build a more granular and robust concept of emotion. Our next steps involve integrating these additional modalities and testing the system in more dynamic, real-world scenarios beyond the lab to see how its understanding holds up amidst the noise and complexity of daily life.

What is your forecast for the future of emotion-aware AI?

I believe we’re on the cusp of a significant shift. For the next five to ten years, we’ll see this technology move from the theoretical to the practical, becoming integrated into assistive technologies and mental health support tools in a very tangible way. We’ll see companion robots that can offer more meaningful, context-sensitive support to the elderly and interactive educational tools that can adapt to a child’s frustration or excitement. The long-term forecast is even more transformative. As these systems become more sophisticated, they won’t just recognize emotion; they will help us understand its very nature. They will become scientific instruments for exploring the human mind, providing a computational framework that finally bridges the gap between psychological theory and empirical validation. We are not just building smarter machines; we are building better tools to understand ourselves.