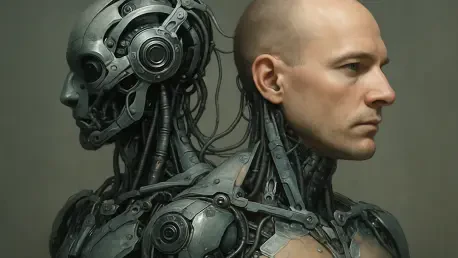

I’m thrilled to sit down with Oscar Vail, a renowned technology expert whose pioneering work in robotics and human-robot interaction is shaping the future of how we collaborate with machines. With a deep passion for emerging fields like quantum computing and open-source innovation, Oscar brings a unique perspective to the fascinating discovery that humans can sense a collaborating robot as part of their own body. In this conversation, we’ll explore the intricacies of human cognition, the unconscious mechanisms behind our interactions with robots, and the implications of these findings for designing more intuitive and effective robotic systems.

Can you explain what the “near-hand effect” is and how it plays a role in human-robot collaboration?

Absolutely. The near-hand effect is a fascinating phenomenon where a person’s visual attention shifts when their hand is close to an object. It’s like the brain is priming itself for action, focusing more intently on what’s near the hand because it might need to interact with it. In the context of human-robot collaboration, this effect becomes really interesting. When a person works alongside a robot, especially on a shared task, their brain starts to treat the robot’s hand similarly to their own. This shift in attention suggests a deeper cognitive integration, where the robot isn’t just a tool but almost an extension of the person’s body.

How does the concept of a “body schema” fit into our interactions with both the environment and robots?

The body schema is essentially an internal map that our brain creates to understand our body’s position and movement in space. It’s what allows us to navigate without constantly looking at our limbs or to use tools seamlessly, like swinging a hammer as if it’s part of us. This map isn’t static—it adapts based on experience. When we studied interactions with robots, we found that the brain can actually incorporate a robot’s hand into this schema during collaborative tasks. It’s remarkable because it shows how flexible our cognition is, extending our sense of self to include non-human elements when they’re useful and familiar.

Can you walk us through the kind of experiment that demonstrates a robot being integrated into a person’s body schema?

Sure, I can describe a typical setup we’ve explored. In one study, participants worked with a child-sized humanoid robot on a joint task—slicing a bar of soap using a wire that they pulled alternately with the robot. The task was chosen because it requires coordination and shared effort, mimicking real-world collaboration. After the activity, we used a specific test to measure attention shifts, placing objects near the robot’s hand and observing how quickly participants reacted to visual cues nearby. The faster responses near the robot’s hand indicated that their brain had started treating it like their own, showing integration into their body schema.

What have you learned about how people perceive a robot’s hand after working closely with it on a task?

The findings are quite compelling. After collaborating, many participants showed a clear cognitive shift—they reacted to stimuli near the robot’s hand as if it were their own, suggesting their brain had mapped it into their personal space. Not everyone experienced this equally, though. The effect was stronger for those who felt a connection with the robot or when the robot’s movements were smooth and synchronized with theirs. Physical proximity also mattered—the closer the robot’s hand was during the task, the more pronounced the integration became. It highlights how context and interaction quality shape perception.

How do people’s feelings or attitudes toward a robot influence this cognitive integration?

That’s a critical piece of the puzzle. We’ve noticed that when participants view the robot as competent or likable, the integration of its hand into their body schema is much stronger. It’s almost as if trust and positive perception lower the mental barriers, allowing the brain to accept the robot as part of their extended self. Empathy plays a role too—when people attribute human-like traits or emotions to the robot, that cognitive bond deepens. It shows that emotional and social factors are just as important as technical design in fostering effective collaboration.

Why do you believe understanding this integration of robots into our body schema is so significant for the future?

It’s hugely important because it opens up new ways to design robots that work seamlessly with humans. If we can create machines that our brains naturally accept as extensions of ourselves, interactions become more intuitive and efficient. This could revolutionize fields like rehabilitation, where robots assist with motor recovery, or assistive technologies for people with disabilities. Even in virtual reality, this understanding could help craft more immersive experiences. Ultimately, it’s about building technology that aligns with human cognition, making collaboration feel effortless and natural.

What is your forecast for the future of human-robot interaction based on these insights?

I’m incredibly optimistic. I think we’re heading toward a future where robots aren’t just tools but true partners in a cognitive and emotional sense. As we refine designs to enhance synchronization, proximity, and social perception, robots will integrate even more deeply into our daily lives. We’ll likely see breakthroughs in personalized robotic systems that adapt to individual users’ body schemas and emotional cues, making them indispensable in healthcare, education, and beyond. The boundary between human and machine will continue to blur, creating partnerships that amplify our capabilities in ways we’re only beginning to imagine.