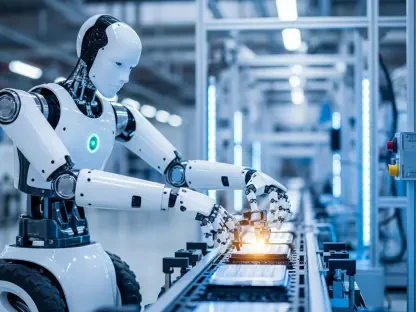

Oscar Vail is a technology expert whose work sits at the fascinating intersection of developmental psychology and robotics. He and his team are pioneering a new “meta-learning framework” designed to teach robots how to physically interact with the world not by programming them with rigid instructions, but by allowing them to learn through touch and sensation, much like a human infant. This interview explores the core principles behind this infant-inspired approach, delving into how robots can develop a sense of their own “space-force boundary” without complex models. We will discuss the unique challenges of a purely data-driven methodology, the key performance differences compared to traditional robotics, and the promising future applications in fields that demand a safer, more natural human-robot partnership.

Your research is uniquely inspired by how human infants learn. Can you elaborate on which specific developmental behaviors you modeled? For example, walk us through how the robot’s “inductive-inference-based training” mimics a baby’s trial-and-error process when first touching an unknown object.

That’s really the heart of our work. We looked at how infants learn before they have any concept of physics or object properties. A baby doesn’t calculate forces; they learn through pure, raw experience. Our “inductive-inference-based training” is a direct digital parallel to that. Think about a baby reaching out to a toy. They don’t know if it’s hard, soft, or heavy. They simply extend their hand, make contact, and their brain processes the flood of sensory information—the pressure on their skin, the resistance, the texture. Our robot does the same. It uses its tactile sensors as its “skin” and proprioception to know where its “hand” is in space. Through countless interactions, it builds a bottom-up understanding. It learns, “when my arm is in this position and I move it this way, I feel this kind of pressure.” It’s a process of pure trial and error, inferring the rules of physical interaction from sensory data alone, without any pre-programmed models telling it what to expect.

The article mentions your framework helps robots estimate the “space-force boundary.” Could you explain this concept in practical terms? Please describe the step-by-step process of how the robot integrates tactile and proprioceptive data to interact safely and naturally with a person.

The “space-force boundary” is a concept we developed to describe the robot’s learned understanding of where it ends and the world begins, not just spatially but in terms of physical force. It’s the key to safe interaction. The process is quite intuitive. First, the robot initiates a movement, constantly tracking its arm’s position in 3D space using proprioception—its internal sense of body position. As it moves, its tactile sensors are streaming data, essentially reporting “no contact.” The moment a tactile sensor registers pressure—say, from touching a person’s shoulder—the framework creates a data point. It links that specific spatial coordinate with the force and other tactile properties it detected. This happens over and over. By integrating thousands of these contact points, the robot builds a rich, dynamic map. This isn’t a static, pre-defined map; it’s a learned boundary that allows the robot to anticipate contact and modulate its force. So, when interacting with a person, it’s not just following a trajectory; it’s actively “feeling” for that boundary to ensure its touch is gentle and natural, not rigid and mechanical.

A key advantage noted is that your framework operates without detailed mechanical models, relying only on sensor data. What were the biggest challenges this data-driven approach presented during development, and could you share an anecdote about a surprising behavior the robot learned as a result?

Moving away from mechanical models is liberating, but it also presents the “blank slate” problem. The biggest challenge was managing the initial learning phase. Without a model, the robot has no predictive power at the start. It doesn’t know that bumping into a table is different from touching a balloon. We had to design the active-learning process very carefully to guide its exploration in a safe and productive way, ensuring it gathered useful data without damaging itself or its surroundings. It was a delicate balance. I remember one surprising moment during an early test. We gave the robot a soft, pliable object to interact with. A robot with a rigid model would likely have just crushed it or failed the task. But our robot, after a few tentative pokes, learned the object’s deformable nature. It started applying a gentle, inquisitive pressure, almost mapping the object’s “squishiness.” It learned a nuanced interaction that we never explicitly programmed. That was a powerful moment for us; it felt less like a machine executing code and more like an organism genuinely learning from sensory feedback.

The article describes your work as a “meta-learning framework” that shapes how robots learn. How does this differ from traditional training methods? Please share some performance metrics that show how much more quickly or effectively a robot can adapt to a new physical task.

The difference is fundamental. Traditional training is about mastering a single, specific task. You can spend weeks training a robot to pick up a certain screw from a specific bin, and it will become incredibly efficient at that one job. But if you change the screw or the bin, the training often falls apart. It’s like cramming for one specific test. Our meta-learning framework, on the other hand, doesn’t teach the robot the task itself; it teaches it the process of learning physical tasks. It’s about building a generalized intelligence for physical interaction. The most significant performance metric we see is its adaptability, specifically its capacity for “few-shot and few-epoch learning.” This means after its foundational training, the robot can adapt to a new object or a new type of interaction with very little new data—sometimes after just a handful of attempts. Where a traditionally trained robot might need thousands of new examples, ours can continuously optimize its behavior on the fly. This ability to evolve and adapt in real-time is what truly sets it apart.

What is your forecast for the integration of this infant-inspired learning into everyday robotics?

I am incredibly optimistic about the future of this approach. In the near term, I see the most profound impact in collaborative robotics, or “cobots,” particularly in healthcare and advanced manufacturing. Imagine a physical therapy robot that can adapt its support to a patient’s unique and changing needs, or an elder-care robot that can provide gentle physical assistance safely. These are scenarios where a pre-programmed, rigid robot is not just ineffective but dangerous. This framework provides that missing piece—the ability to learn and adapt through touch. The next critical milestone for us is scaling. We need to rigorously test this on a wider variety of robotic platforms and in more complex, unstructured environments. Once we prove its robustness and reliability at scale, I believe this infant-inspired learning will become a foundational technology, paving the way for robots that can finally move out of cages and work alongside humans in a truly natural, safe, and collaborative way.