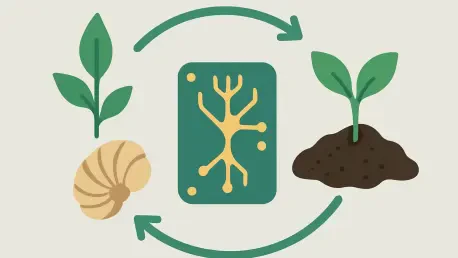

Today, we’re speaking with technology expert Oscar Vail about a groundbreaking development in sustainable electronics: a fully biodegradable artificial synapse. This tiny device, crafted from natural materials like shells and plant fibers, mimics the human brain’s efficiency and holds the potential to solve the ever-growing problem of electronic waste. We’ll explore how this “tiny sandwich” of natural polymers achieves record-breaking memory, operates on less energy than a biological synapse, and can break down in soil in just over two weeks. We will also discuss a fascinating real-world demonstration involving a robotic reflex and look at what this innovation means for the future of eco-friendly, intelligent systems.

Your team sourced materials from shells, beans, and plant stems to create a “tiny sandwich” structure. Could you walk us through how these natural polymers are assembled? What specific properties of cellulose acetate and chitosan made them ideal for creating the device’s memory function?

It’s a process that really takes its cues from nature itself. We built the device as a layered structure, much like a tiny, intricate sandwich. The core of this is the ion-binding layer, which we created from cellulose acetate derived from plant stems. On either side of this, we place ion-active layers, which utilize materials like chitosan, a polymer we get from shells. When we apply an electrical signal, sodium ions—which act like the neurotransmitters in our own brains—are released and travel through these layers. The cellulose acetate is crucial because its structure is perfect for temporarily trapping or binding these ions, while the chitosan facilitates their movement. This interplay is what allows us to create and hold a memory state within the device.

The synapse achieves a record memory of nearly 100 minutes using “ion dipole coupling.” Could you explain this mechanism in more detail? What was the key breakthrough that allowed you to extend memory retention so significantly beyond previous biodegradable devices?

The “ion dipole coupling” is really the secret sauce here. When an electrical pulse stimulates the synapse, it causes sodium ions to move and bind at the interfaces between the different polymer layers. The breakthrough wasn’t just in making them move, but in what happens after the stimulation stops. Our material design allows a certain number of these ions to remain bound at the interface, creating a residual state. This retained charge is essentially the memory. This process allows the device to hold information for an extended period—we’ve clocked it at nearly 6,000 seconds, or about 100 minutes. For a fully biodegradable device, that’s an unprecedented duration, and it’s this robust retention that moves us from fleeting, short-term memory to a much more useful long-term plasticity.

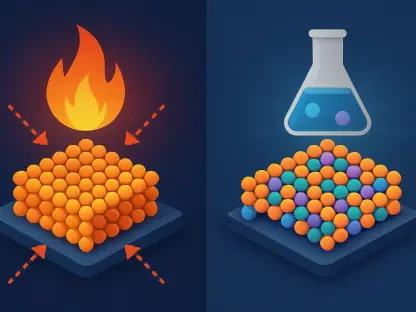

The energy efficiency is remarkable, using only 0.85 femtojoules per signal—less than a biological synapse. What specific aspects of the design contribute to this ultra-low power consumption, and what challenges did you overcome to achieve this level of efficiency?

Achieving that level of efficiency was a primary goal, and it’s deeply connected to the ionic mechanism we’ve been discussing. Our own brains are incredibly efficient because they use ions, not a brute-force flow of electrons. We mimicked that. The device only needs a tiny electrical nudge to get the sodium ions moving, and the “ion dipole coupling” effect is a very low-energy way to store a state. We’re talking about just 0.85 femtojoules per synaptic event, which is incredible when you consider a biological synapse uses between 2.4 and 24 femtojoules. The main challenge was achieving stability. It’s one thing to make a device that’s sensitive to low energy, but it’s another to make it durable and reliable so it doesn’t fire accidentally or degrade its performance over time. Balancing that sensitivity with robustness was the tightrope we had to walk.

You demonstrated a robotic reflex system where the synapse triggers a hand to withdraw from heat. Could you detail the signal pathway, from the thermistor’s initial detection to the synapse’s processing and the final robotic action?

That demonstration was a really exciting proof-of-concept. The system is designed to mimic a simple biological reflex arc. It starts with a thermistor, which acts as the sensory neuron, detecting a change in temperature—in this case, a hot object. The thermistor sends an initial, weak electrical signal to our artificial synapse. This is where the magic happens. The synapse, acting as the processor, receives this signal, and the ion movement inside amplifies it significantly, creating a much stronger output signal. This amplified signal is then sent to the robotic hand, the actuator, triggering it to withdraw immediately. It’s a seamless flow from sensing to processing to action, all orchestrated by our biodegradable synapse, just as a real nervous system would react to a painful stimulus without conscious thought.

The device fully biodegrades in soil within 16 days. Can you describe the decomposition process for the key materials? What does this rapid, clean breakdown mean for the future of single-use or environmentally integrated electronics?

The beauty of using materials like cellulose acetate and chitosan is that they are already part of nature’s cycle. When we place the device in soil, microorganisms recognize these polymers as a food source. They simply break them down into their basic, harmless building blocks over a very short period—we observed a complete breakdown in just 16 days. There are no toxic chemicals or heavy metals left behind. This is transformative for electronics. Imagine single-use medical sensors that dissolve after use, or environmental monitors scattered in a forest that perform their task and then simply return to the earth. It fundamentally changes our relationship with technology, from creating permanent waste to designing devices that can have a temporary, functional life and then disappear without a trace.

What is your forecast for the field of biodegradable neuromorphic technologies over the next decade?

I believe we are on the cusp of an era where electronics will be designed to coexist with the environment, not pollute it. Over the next ten years, I forecast that we’ll see these biodegradable neuromorphic technologies move from the lab into specialized, high-impact applications. We’ll see them in “smart agriculture,” where sensors can monitor soil conditions and then decompose. They’ll appear in temporary medical implants that assist healing before being safely absorbed by the body. We will likely also see them in soft robotics designed for environmental cleanup, where the robots can complete their mission and then biodegrade. The focus will shift from making electronics that last forever to making intelligent electronics that last for exactly as long as they are needed, paving the way for a truly sustainable technological ecosystem.