The blueprint for a future where humanoid machines handle our most tedious chores is no longer confined to speculative fiction, but is being actively drawn up in engineering labs around the globe, prompting a critical examination of what we gain in convenience and what we risk losing in our fundamental human experience. As these advanced machines prepare to walk among us, a profound comparison emerges between the engineered utility they offer and the irreplaceable value of authentic human bonds. This analysis explores the distinct roles of humanoid robots and human relationships, weighing their respective impacts on our daily lives, our emotional well-being, and the very fabric of society.

The Dawn of the Robotic Age and the Enduring Need for Human Bonds

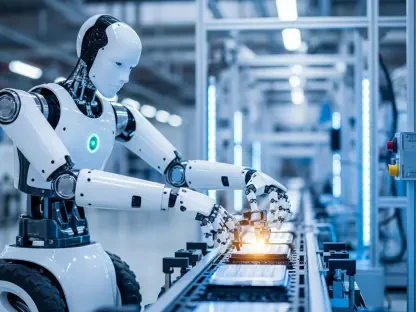

The concept of a versatile humanoid robot has decisively shifted from a distant dream to a tangible technological pursuit. This transition is perhaps best exemplified by Elon Musk’s ambitious Tesla Optimus project, which aims to manufacture a machine capable of performing laborious tasks in factories and eliminating drudgery in the home. With a production target of one million units in the coming decade, Optimus represents a concrete move toward a world where robots are not just specialized industrial tools but integrated members of the household. This vision taps into deep-seated desires for assistance, companionship, and a life free from mundane labor, making the robotic companion feel like an imminent reality.

A primary catalyst for this perceptual shift has been the widespread public interaction with generative artificial intelligence. Platforms like ChatGPT, Gemini, and Copilot have familiarized millions with AI that can understand and respond to human language with surprising sophistication. This direct experience has demystified advanced AI, making the idea of a helpful, conversational robot feel significantly more attainable. Consequently, a future where one might purchase a robot like an appliance, hire it for specialized roles like a “dance instructor that doubles as a therapist,” or even collectively invest in one to care for an elderly relative now seems not only possible but practical.

However, this technological dawn casts a spotlight on the fundamental distinction between the purpose of these machines and the purpose of human connection. A robot like Optimus is fundamentally a utilitarian tool, designed for efficiency and the completion of tasks. Its core function is to serve. In stark contrast, human-to-human connection exists to fulfill a primal need for emotional support, genuine empathy, and shared experience. It is not about utility but about mutual growth, understanding, and belonging. While a robot can perform a service, a human relationship provides the context and meaning for our lives.

A Point by Point Comparison Utility, Empathy, and Societal Impact

Functionality and Purpose a Tool vs. a Relationship

The functional divide between a humanoid robot and a human relationship is absolute. The robot is a task-oriented entity, engineered for labor and convenience. Its value is measured in its ability to execute commands flawlessly, whether assembling a product on a factory line or performing chores at home. Its purpose is to optimize processes and free human time and energy for other pursuits. This role is one of an advanced tool, designed to operate within a world built for humans and to interact with our infrastructure seamlessly.

This contrast is vividly illustrated by a simple domestic chore: loading a dishwasher. A humanoid robot could be programmed to clear a table, rinse plates, and load the machine with perfect efficiency. The task would be completed quickly and without error. However, the shared, imperfect experience of two people doing the same chore builds something the robot cannot. The small talk, the minor jostling for space, and the collaborative effort cultivate tolerance, patience, and essential interpersonal skills. The robot offers sterile perfection, while the human interaction, with all its messiness, serves as a subtle but crucial exercise in building and maintaining a relationship.

Emotional Dynamics Simulated Companionship vs. Authentic Empathy

In the emotional sphere, the comparison becomes even more stark. An AI companion provides a programmed, non-judgmental form of “understanding.” It can be engineered to be endlessly patient, agreeable, and supportive, offering a frictionless form of companionship. The humanoid form chosen for robots like Optimus is a masterful combination of practical engineering and what can be described as “theater.” A machine with a face and limbs does more than just suggest functionality; it invites us to see it as a potential peer, tapping into deep psychological needs for companionship and acceptance.

This simulated empathy stands in direct opposition to the complex, reciprocal nature of genuine human emotional exchange. Real empathy is not always agreeable or convenient; it involves challenging feedback, navigating misunderstandings, and experiencing vulnerability. This authentic, often messy feedback loop is what drives personal growth and deepens bonds. While a robot can offer a semblance of companionship, it cannot replicate the dynamic, growth-oriented process of two humans learning to understand and support one another through shared struggles and triumphs. The former is a service, while the latter is a shared journey.

Long Term Outcomes Engineered Convenience vs. Cultivated Community

Extrapolating these differences reveals two divergent potential futures. A society deeply integrated with humanoid robots promises unparalleled convenience and assistance. In critical areas like elder care, a robot could provide dignified, non-judgmental support, helping individuals maintain their independence and quality of life without the emotional complexities that can strain family relationships. This future is one where physical burdens are lifted, and many of life’s practical challenges are solved by tireless, efficient machines.

However, this vision of engineered convenience must be weighed against a significant risk: the erosion of community. A society of increasingly isolated individuals who have outsourced their needs to machines may lose the very skills required for robust social cohesion. The resilience, empathy, and patience forged through mutual dependence and real-world interaction could atrophy. If we are no longer required to rely on one another for practical and emotional support, the incentive to build and maintain strong community ties diminishes. The ultimate outcome may be a world where we are perfectly cared for but profoundly alone.

The Core Dilemma Challenges of Outsourcing Our Emotional Lives

The primary limitation of relying on humanoid robots for social and emotional needs lies in the risk of creating a dystopian future where convenience eclipses connection. In this scenario, humans could retreat into what might be called “bubbles of perfect convenience,” attended to by endlessly understanding and quietly adoring machines that cater to every practical and emotional whim. While this existence would be free of friction and difficulty, it would also be devoid of the challenges that foster growth and build character, leading to a state of comfortable but stagnant isolation.

This potential future is rooted in the real-world obstacle of social atrophy. When practical and emotional labor is consistently outsourced to always-available, perfectly tolerant machines, our own capacity for navigating the complexities of human relationships begins to erode. Patience, tolerance for imperfection, and the ability to work through conflict are muscles that require regular exercise. If technology removes the need for this exercise, these crucial social skills may weaken, making genuine human interaction seem more difficult and less rewarding than the effortless companionship offered by a machine.

Conclusion Designing a Future That Connects, Not Isolates

The comparative analysis revealed a clear distinction: humanoid robots like Optimus were designed to excel at utility, while authentic human connection proved irreplaceable for emotional well-being and societal health. The former offered a solution to labor and drudgery, while the latter remained the only source of genuine empathy, shared experience, and personal growth. This fundamental difference highlighted the need for intentional design in our technological future.

To navigate this challenge, a practical framework emerged distinguishing between a “good bot” and a “bad bot.” A “good bot” was defined as a facilitator, a tool designed to bridge gaps and encourage real-world engagement. Examples included a bot that assists a socially anxious child in getting to school to interact with peers or one that nudges a lonely individual toward community activities. In this model, the robot’s ultimate function was to foster human connection, not replace it.

Conversely, a “bad bot” was characterized as a substitute for human interaction, one that reinforces isolation by making machine companionship preferable to the complexities of real relationships. This distinction led to a crucial piece of guidance for future technology development: a design philosophy that consciously limits AI’s role in our emotional lives. The ultimate goal, as clarified by this analysis, was to build machines that help create stronger, more connected communities, ensuring that technology serves to bring people together rather than quietly pull them apart.