I’m joined today by Oscar Vail, a technology expert with a keen interest in emerging fields such as quantum computing, robotics, and open-source projects. With a consistent position at the forefront of industry advancements, he’s here to discuss a concerning new development where personal AI assistants have become the latest target for malware. This conversation will explore the fundamental security weaknesses in how these AI agents integrate with our digital lives, the real-world implications of a recent attack, and what it truly means to have an AI’s “identity” stolen. We will also look ahead to the escalating cyber threats on the horizon as these intelligent tools become more common.

Open-source AI assistants like OpenClaw manage tasks by connecting to personal apps using API keys. Could you walk us through how this integration works and describe the specific security vulnerabilities created when these sensitive authentication tokens are stored in local configuration files on a user’s machine?

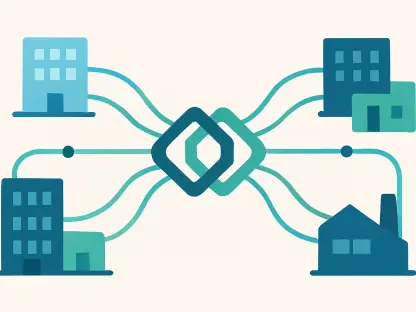

Of course. Think of an API key as a special key that lets two different applications talk to each other securely. When you set up an AI assistant like OpenClaw, you’re essentially giving it a set of these keys to access your other services—your calendar, your Telegram, your email, and so on. The vulnerability isn’t in the concept of using keys, but in where they are stored. OpenClaw, being an open-source tool set up on a personal computer, stores these secrets in local configuration files. This is the digital equivalent of writing down all your passwords on a sticky note and leaving it on your desk. If any malware gains access to your computer, it doesn’t need to be sophisticated; it just needs to know where to look for that file, and suddenly it holds the keys to your entire connected workflow.

A recent incident saw an infostealer exfiltrate an OpenClaw configuration file as part of a wider data grab. Could you explain the difference between this kind of opportunistic theft and a targeted attack? Please detail what kind of access an attacker gains from these stolen files.

That’s a critical distinction. What we saw in this first incident was opportunistic theft. The infostealer was designed to be a digital vacuum cleaner, sucking up as many sensitive files as it could from the infected system without a specific goal in mind. It just happened to grab the OpenClaw configuration file along with everything else. A targeted attack, on the other hand, would be a precision strike. The malware would be specifically coded to hunt for OpenClaw files. Once an attacker has these files, they gain direct access to whatever the AI agent was connected to. They could read your private Telegram messages, manipulate your calendar to schedule malicious meetings, or automate harmful workflows, all under the guise of your trusted AI assistant.

The attack is being described as stealing the “soul” of a personal AI agent. What does this metaphor mean in a practical sense for a user or a business? Can you provide an example of how an attacker could leverage this stolen “identity” for malicious purposes?

The “soul” metaphor is incredibly fitting because the configuration file contains the agent’s identity and its trusted relationships. It’s not just about stealing a password; it’s about stealing the entity that has permission to act on your behalf. For a business, imagine an AI assistant is used to manage a project’s communication on Telegram and its scheduling via a shared calendar. An attacker with its “soul” could subtly inject misinformation into team chats, delete critical meetings from the calendar, or even use the agent’s email access to send out phishing links to the entire team. Because the actions would originate from a trusted source—the AI agent—they would likely go unnoticed until significant damage was done.

Experts predict infostealers will soon develop modules to specifically parse AI agent data, similar to how they target browsers today. Could you describe what this evolution looks like in practice? Please explain the technical steps malware developers would take to build and deploy such a module.

This evolution is the logical next step for cybercriminals. Right now, infostealers grab browser cookies and saved passwords because that’s where the value has been. As AI agents become more valuable, developers will release updated malware with new modules. The first step is reverse-engineering how an agent like OpenClaw stores its data to identify the exact file names and data structures. Next, they’ll write a specific function—the module—that searches for these files on an infected machine. This module would then be programmed to decrypt or parse the configuration data, neatly extracting the API keys and authentication tokens. Finally, they’d package this new module into their existing infostealer and deploy it, creating a much more efficient and dangerous tool for harvesting AI agent identities.

What is your forecast for the security landscape of personal AI agents as they become more integrated into our professional and personal workflows?

My forecast is that we are at the very beginning of a new cybersecurity battlefront. As AI agents move from novelties to indispensable tools in our professional lives, the incentive to attack them will skyrocket. We will see a rapid evolution from the current opportunistic attacks to highly targeted campaigns designed to compromise corporate workflows through these agents. The security industry will have to race to develop new standards for how these agents store secrets and authenticate themselves. In the near future, securing your personal AI will be just as critical as securing your email or your bank account, because it will soon hold the keys to both and much more.