The boundless energy potential contained within the ocean’s natural temperature variations is now being unlocked by a technology that cleverly merges 19th-century physics with 21st-century material science and engineering. The technology of marine thermomagnetic generators represents a significant advancement in the autonomous maritime systems sector. This review will explore the evolution of the technology, its key features, performance metrics, and the impact it has on various applications. The purpose of this review is to provide a thorough understanding of the technology, its current capabilities, and its potential future development.

Fundamentals of Thermomagnetic Energy Conversion

The Curie Effect as a Guiding Principle

The operational heart of a thermomagnetic generator lies in a fundamental physical principle known as the Curie effect. This phenomenon describes the temperature at which certain magnetic materials undergo a sharp change in their magnetic properties. The specific temperature for this transition is called the Curie point. Below this temperature, a ferromagnetic material exhibits strong magnetic attraction; above it, the material becomes paramagnetic, losing its permanent magnetism.

A thermomagnetic generator exploits this transition by cyclically heating and cooling a ferromagnetic material around its Curie point. As the material is warmed by a heat source, it loses its magnetism. When cooled, it regains its magnetic properties. This continuous switching between magnetic and nonmagnetic states creates a fluctuating magnetic field, or magnetic flux. According to Faraday’s law of induction, a changing magnetic flux through a nearby conductive coil induces an electrical current. This process allows for the direct conversion of thermal energy into electrical power without complex mechanical parts, offering a solid-state energy harvesting solution.

Historical Foundations from Tesla to Modern Realizations

The concept of harnessing thermal energy through magnetism is not a recent discovery; its roots extend back to the pioneering age of electricity with visionaries like Nikola Tesla and Thomas Edison. Both inventors filed patents on devices designed to achieve thermomagnetic generation, envisioning them as a novel way to produce electricity. However, their ambitious goal was to generate power on an industrial scale, targeting megawatt outputs for widespread use.

Subsequent analysis revealed that the technology was fundamentally inefficient and impractical for such large-scale applications, leading to its general abandonment for nearly a century. The contemporary resurgence of this concept is driven by a strategic paradigm shift. Instead of pursuing high power output, modern research, such as the work conducted at the National Laboratory of the Rockies (NLR), focuses on miniaturization and low-power applications. The goal is no longer to power cities but to energize the vast, distributed networks of wireless sensors that form the backbone of modern environmental monitoring.

Core Design and Material Science

Gadolinium as the Optimal Ferromagnetic Material

The selection of the active material is critical to the performance of a thermomagnetic generator, as its Curie point must align with the available environmental temperatures. For marine applications, researchers have identified gadolinium, a rare earth element, as a nearly perfect candidate. Gadolinium possesses a Curie point conveniently located near room temperature (around 20°C or 68°F), making it highly sensitive to the subtle temperature differences found in the ocean environment.

In addition to its ideal Curie temperature, gadolinium exhibits strong ferromagnetic properties, meaning its magnetic state changes dramatically during the phase transition. This pronounced change maximizes the fluctuation in the magnetic flux, which directly translates to a more significant electrical current being generated. The choice of gadolinium is therefore a cornerstone of the modern prototype’s design, enabling efficient energy conversion within the specific thermal conditions of the maritime setting.

Miniaturized Design for Low-Power Applications

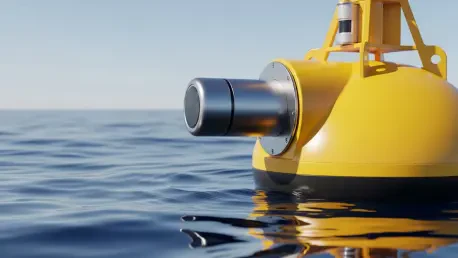

The shift in focus from macro-generation to micro-generation has enabled a complete reimagining of the generator’s physical form. Modern prototypes are compact and designed for integration into small, autonomous platforms like sensor buoys. The NLR team, for instance, developed a device small enough to be tested in a 15-gallon aquarium, with the final deployable version anticipated to be approximately a foot in length.

This miniaturization is tailored for the milliwatt power range required by contemporary wireless sensors and data transmitters. By scaling the technology down, researchers have transformed an inefficient concept for large-scale power into a highly practical solution for low-power, remote applications. This approach avoids the need for bulky batteries with limited lifespans, offering a pathway toward truly self-sustaining, long-term maritime monitoring systems.

Harnessing Low-Grade Marine Thermal Gradients

One of the most compelling features of this technology is its ability to operate effectively using low-grade thermal energy, which is abundant but difficult to harvest with other methods. The generator is engineered to function on the small temperature difference, often less than 10 degrees, between the ocean surface water and the ambient air. This thermal gradient provides the necessary heating and cooling cycle for the gadolinium core.

Remarkably, the system’s design is robust enough to generate power even when the water and air temperatures are nearly identical. In such conditions, the natural process of evaporative cooling, enhanced by wind moving across the device’s surface, can lower the gadolinium’s temperature just enough to cross its Curie point. This resilience ensures consistent and reliable power generation across a wide range of marine weather conditions, making it a dependable energy source for persistent, year-round operation.

Recent Innovations and Research Validation

NLRs Prototype Development and Performance

Recent advancements in this field are exemplified by the prototype developed by researchers at the National Laboratory of the Rockies. Their work, detailed in the journal Communications Engineering, presents a functional thermomagnetic generator designed specifically for marine thermal energy harvesting. The research outlines the scientific principles, engineering design, and, most importantly, the validated performance of their device.

The NLR team has successfully demonstrated that their generator can produce the necessary electrical power to operate typical maritime sensors. This achievement marks a critical milestone, moving the technology from a theoretical concept to a proven, functional system. The project showcases how modern material science and precision engineering have overcome the historical limitations of thermomagnetic generation, validating its potential as a groundbreaking energy solution for specific, targeted applications.

Validating Power Generation in Controlled Environments

Before any technology can be deployed in the unpredictable ocean environment, it must first prove its capabilities under controlled laboratory conditions. The NLR generator has undergone rigorous testing, starting with initial evaluations in an aquarium and progressing to more extensive trials in a water tank. These tests were designed to simulate marine thermal gradients and validate the device’s power output and operational stability.

The successful outcomes of these controlled experiments provided the essential proof-of-concept needed to advance the project. By consistently generating the target amount of power in a simulated environment, the researchers have built a strong foundation of data supporting the generator’s viability. This validation phase is a crucial step in the research and development process, providing the confidence to move forward toward real-world field testing.

Applications in Maritime Sensing and Exploration

Powering Autonomous Buoys and Remote Sensors

The primary application for marine thermomagnetic generators is to provide a continuous, autonomous power source for remote sensing equipment. Oceanographic buoys, underwater sensors, and other unmanned maritime systems currently rely on batteries or solar panels. Batteries require periodic and costly replacement, while solar power is dependent on weather and daylight, limiting its reliability in many marine locations.

By integrating a thermomagnetic generator, these platforms can become fully self-sustaining. The generator would continuously recharge a small battery or capacitor, ensuring an uninterrupted power supply for sensors measuring water temperature, salinity, currents, and atmospheric conditions. This capability promises to significantly reduce the operational costs and logistical challenges associated with maintaining remote ocean monitoring networks.

Enabling Long-Term Uninterrupted Ocean Data Collection

The ability to power sensors indefinitely opens new frontiers for oceanography and climate science. Current data collection efforts in remote oceanic regions are often constrained by the power limitations of monitoring devices. This can lead to gaps in data, hindering scientists’ ability to track long-term trends and understand complex marine processes.

Thermomagnetic generators offer a solution to this challenge by enabling persistent, multi-year deployments without human intervention. This would allow for the collection of continuous, high-resolution data from even the most inaccessible parts of the ocean. Such datasets are invaluable for improving climate models, monitoring marine ecosystems, and enhancing our overall understanding of the planet’s oceans.

Challenges and Overcoming Environmental Hurdles

Ensuring Durability in Harsh Ocean Conditions

The ocean is an exceptionally hostile environment for any engineered system. Saltwater is highly corrosive, waves exert immense physical stress, and biofouling—the accumulation of marine organisms on surfaces—can impede mechanical and thermal functions. For a thermomagnetic generator to be successful, it must be designed to withstand these harsh realities for extended periods.

Researchers are actively addressing these durability challenges through advanced material selection and protective measures. The development of specialized coatings is a key focus, as these can prevent corrosion and inhibit biofouling. Furthermore, the generator’s enclosure must be robustly engineered to survive the mechanical forces of storms and strong currents, ensuring its structural integrity over a multi-year deployment.

Transitioning from Laboratory Prototypes to Field Deployment

The transition from a controlled laboratory setting to the dynamic, unpredictable ocean is one of the most significant hurdles in marine technology development. While a prototype may perform flawlessly in a test tank, its performance in the real world can be affected by a multitude of unforeseen variables.

The next critical phase for the NLR team and others in this field involves comprehensive field testing in an actual ocean environment. This step is essential to evaluate the generator’s real-world efficiency, long-term durability, and overall performance. The data gathered from these deployments will be vital for refining the design, validating its practical application, and ultimately proving its readiness for commercial and scientific use.

Future Outlook and Technological Trajectory

The Path toward Real-World Ocean Deployment

With laboratory validations successfully completed, the immediate future for marine thermomagnetic generators is focused on ocean-based trials. These field tests will provide the ultimate assessment of the technology’s resilience and effectiveness. Success in this phase would pave the way for pilot programs where generators are integrated into existing sensor networks for long-term evaluation.

Looking further ahead, from 2026 to 2028, the trajectory will likely involve scaling up production, refining the design for cost-effectiveness, and developing standardized models for different types of maritime platforms. Collaboration between research institutions, government agencies, and commercial partners will be crucial to accelerating this transition from a research prototype to a widely adopted technology.

Potential Impact on Oceanography and Offshore Industries

The successful deployment of this technology could have a transformative impact across several sectors. In oceanography and climate science, it would enable the creation of more extensive and persistent global ocean observing systems, providing data of unprecedented quality and duration. This would fundamentally enhance our ability to monitor and predict changes in the Earth’s climate system.

Beyond scientific research, the offshore energy and maritime navigation industries also stand to benefit. Thermomagnetic generators could power remote navigation aids, monitoring equipment for offshore platforms, and sensors for aquaculture operations. By providing a reliable, maintenance-free power source, the technology offers a compelling solution for increasing the autonomy, safety, and efficiency of a wide range of offshore activities.

Conclusion

Summary of Technological Advancements

The technology of marine thermomagnetic generators represents a clever revitalization of a historic concept, now made viable through modern material science and a focus on low-power applications. The core innovation lies in using materials like gadolinium, whose Curie point aligns with marine thermal gradients, to create a simple, solid-state energy harvester. Successful laboratory prototypes demonstrate the capacity to generate sufficient power for remote sensors by harnessing subtle temperature differences, a feat that establishes a new paradigm for powering autonomous maritime systems. This progress signals a significant step away from reliance on finite power sources like batteries, pointing toward a future of self-sustaining ocean monitoring.

Final Assessment of Marine Thermomagnetic Generators

The development of the marine thermomagnetic generator marked a significant and innovative step forward in the field of energy harvesting. The research successfully validated the principle of using the Curie effect to convert low-grade thermal energy into usable electricity for a targeted, high-impact application. While the journey from a proven prototype to widespread ocean deployment presented substantial engineering challenges related to durability and environmental resilience, the foundational technology proved to be sound and promising. The project not only delivered a potential solution for powering remote maritime sensors but also reignited interest in a field of physics that had been dormant for decades, showcasing how a change in scale and application can transform a forgotten idea into a modern technological breakthrough.