The quest to create a true synthetic muscle—one that rivals the strength, speed, and efficiency of our own—has long been a “Holy Grail” in materials science. Recently, a breakthrough from researchers at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln has brought us a significant step closer with a novel hydrogel actuator featuring an integrated microfluidic “circulatory system.” To unpack the significance of this advancement, we sat down with technology expert Oscar Vail. Our conversation explores how this new material mimics biological principles, its potential to revolutionize soft robotics and prosthetics, and the remaining challenges on the path to creating truly lifelike artificial muscle.

Your work on a new synthetic muscle combines hydrogels with a microfluidic ‘circulatory system’. Can you walk us through how this system delivers chemical stimuli, and what specific performance improvements, like response time, this design achieves compared to traditional hydrogels that must be submerged in water?

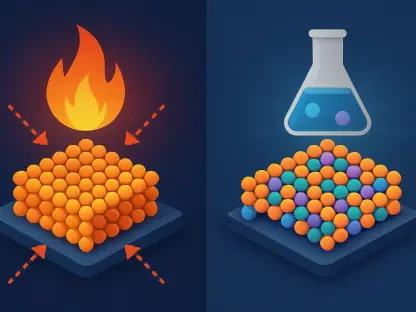

The ‘circulatory system’ is the real game-changer here. Imagine traditional hydrogels as sponges; to get them to actuate or move, you had to dunk the entire thing in a chemical bath and wait for the stimulus to slowly soak in. It was incredibly inefficient and, of course, meant the device could only work underwater. This new design embeds a network of microfluidic channels—essentially tiny blood vessels—directly into the material. These channels deliver chemical or thermal fuel right to the tiny hydrogel units, or microgels, that do the work. The result is a much faster, more direct response, and it frees the actuator from its aquatic prison, allowing it to function in non-aqueous environments, which is critical for almost any real-world application.

Biological muscle is incredibly efficient and adaptable. You’ve identified microstructure and chemical control as key principles in your design. How do these two principles work together in your actuator, and what major hurdles still remain to truly replicate a natural muscle’s impressive force and speed?

These two principles are fundamentally intertwined, just as they are in nature. The “microstructure” refers to the smart arrangement of the tiny microgel units, which are the core components that contract or expand. The “chemical control” is the microcirculatory system we just discussed, which acts as the supply line. You can’t have one without the other for an effective system. The circulatory network delivers the energy, and the microgel structure translates that energy into controlled movement. It’s a beautiful synergy. However, we have to be realistic. While we’ve made a leap in control and response, the major hurdles of force and speed are still formidable. Biological muscle can convert chemical stores like sugars and fats into powerful, split-second contractions. Replicating that level of raw power and energy efficiency remains the ultimate goal and a monumental challenge for the field.

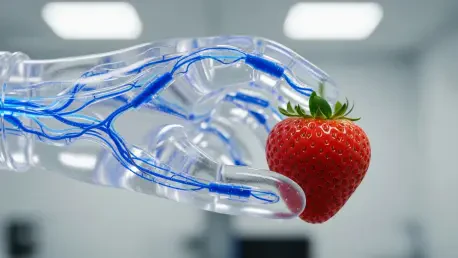

While rigid motors have their place, soft robotics are often envisioned for interacting with people or delicate environments. In what specific scenarios would this synthetic muscle be safer or more effective, and what are the main design challenges in creating a functional soft robotic hand with it?

Absolutely, rigid motors and batteries aren’t going anywhere, but they are often clumsy and potentially dangerous for direct human interaction. This soft, flexible, water-based muscle is perfect for applications where a gentle touch is paramount. Think of a robotic caregiver helping a patient, or a device for harvesting delicate fruit without bruising it. The material itself is compliant and safer. The researchers have already demonstrated proof-of-concept devices like microgrippers and even a soft robotic “hand” capable of programmable motions. The primary design challenge now is scalability and dexterity. To create a truly functional hand, we need to integrate many of these actuators in a complex, coordinated way, ensuring the microfluidic system can service them all to produce the nuanced movements of grasping and manipulation.

The next step appears to be creating fiber-like or tubular shapes to better mimic natural muscle. Could you detail the process for creating these structures, and what new capabilities or efficiencies might be unlocked by organizing these actuators into larger bundles?

This is the most logical and exciting next phase. Our own muscles aren’t flat sheets; they are intricate bundles of long fibers. The plan is to fabricate these hydrogel actuators into similar fiber-like or tubular forms. By doing so, we can then begin to weave them together into larger, more powerful bundles. This is how you truly begin to scale the system for practical use. A single fiber might be weak, but a bundle of hundreds could lift significant weight. This approach doesn’t just increase force; it also opens up possibilities for more complex and hierarchical motions, where different bundles can be activated independently to create a far more sophisticated and lifelike range of movement.

What is your forecast for soft robotics and advanced prosthetics in the next decade?

I believe we’re on the cusp of a major transformation. For years, the field has been limited by materials that were either too slow, too weak, or too dependent on being submerged in water. Breakthroughs like this integrated circulatory system are tearing down those barriers. Over the next ten years, I forecast we will see this technology move from the lab into specialized, high-impact applications. We’ll likely see ultra-gentle robotic grippers in manufacturing and agriculture first, followed by more advanced prosthetic devices that offer a more natural, compliant feel and movement. The ultimate vision of a fully functional, lifelike prosthetic hand or a truly autonomous soft robot is still a ways off, but the foundational work being done today is paving a direct and very promising path to get there.