As humanity continues to map the cosmos, it’s startling to realize that a staggering 74% of our own planet’s ocean floor remains a complete mystery. To chart these hidden depths, we need a new generation of explorers—underwater robots that can navigate where traditional drones falter. Technology expert Oscar Vail, a leading voice in bio-inspired robotics, joins us to discuss the cutting-edge developments in this field. We’ll explore how engineers are drawing inspiration from the elegant efficiency of stingrays, the complex trade-offs in powering these machines at different scales, and the critical next steps toward creating truly autonomous underwater explorers.

Given that so much of the ocean floor remains unexplored, how do ray-inspired robots overcome the stability and maneuverability issues that challenge traditional propeller-driven drones in choppy currents? Please detail the specific advantages of their unique body shape and movement.

It’s a fantastic question that gets to the very heart of why we look to nature for engineering solutions. Traditional propeller drones are powerful, but in complex, turbulent underwater environments, they can really struggle. Their propulsion systems create a lot of water disturbance and can be inefficient when fighting against unpredictable currents. Ray-inspired robots, on the other hand, leverage a completely different philosophy of movement. Their flat, wide bodies are inherently stable, allowing them to glide through the water with incredible efficiency, much like a wing in the air. This shape helps them resist being tossed around by choppy currents. Instead of just pushing through the water, they use their pectoral fins to generate propulsion in a way that is both powerful and graceful, mimicking the oscillatory or undulatory movements we see in real rays. This bio-inspired design is a game-changer for operating in the challenging, dynamic conditions of the deep sea.

Engineers are using diverse actuators, from standard electric motors to smart materials that change shape with an electric pulse. Could you compare the trade-offs of these systems for different robot sizes and describe a scenario where one is clearly superior to the others?

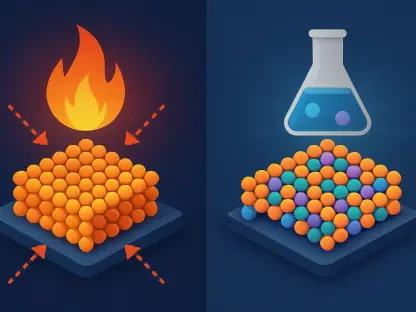

The choice of actuator is one of the most critical design decisions, and it’s almost entirely dictated by the robot’s scale. For large robots, say the size of a dinner plate or bigger, standard electric servos are the go-to solution. They provide the raw power needed for propulsion and are relatively reliable. Imagine a scenario where a robot is tasked with mapping a large section of the seabed; you need the robust, sustained power that these motors provide. On the opposite end of the spectrum, for tiny, coin-sized robots, these motors are far too heavy and rigid. Here, smart materials are clearly superior. These materials, which change shape when an electric pulse is applied, are lightweight and flexible, allowing for the creation of incredibly nimble micro-robots. There are even experimental microscopic designs using living heart cells that contract to create a flapping motion. The trade-off is clear: power and durability for size and weight, versus flexibility and miniaturization for a lack of raw strength.

A significant engineering gap exists for mid-sized robots, where smart materials are often too weak and conventional motors are too heavy. What specific approaches or hybrid technologies are being explored to solve this power-to-weight ratio problem for these crucial intermediate designs?

This is what I call the “unhappy middle,” and it’s a major engineering puzzle right now. You have these mid-sized robots that are too large for the subtle force of smart materials to propel them effectively, but they’re also too small to carry the weight and bulk of conventional motors without a massive performance penalty. It’s a frustrating gap because this intermediate size is incredibly useful for a wide range of applications. Researchers are actively exploring hybrid systems to bridge this divide. This could involve combining smaller, more efficient motors with novel mechanical linkages that amplify their force, or integrating smart materials not for primary propulsion but for fine-tuning control surfaces, like the trim on an airplane wing. The goal is to find a sweet spot that delivers sufficient power without sacrificing the agility and efficiency that make the ray-inspired design so appealing in the first place. The solution isn’t straightforward, but it’s a very active area of research.

Beyond mastering propulsion, the next frontier involves environmental sensing and autonomous navigation. What are the key hurdles in equipping these robots with the AI and sensory abilities to navigate complex, unpredictable underwater environments? Could you walk us through the necessary steps?

We’ve made incredible strides in locomotion, as the review of 47 different ray-inspired robots shows, but movement is only half the battle. A robot that can swim beautifully but has no idea where it is or what’s around it is effectively useless for exploration. The first step is equipping them with a robust sensor suite—sonar, pressure sensors, and high-resolution cameras—to perceive the environment. The next, and much harder, step is developing the artificial intelligence to process that sensory data in real time. The ocean is not a static environment; currents shift, obstacles appear, and visibility can drop to zero in an instant. The AI needs to be able to build a mental map of its surroundings, make intelligent decisions to avoid collisions, and navigate toward its objective without human intervention. This involves complex algorithms for pathfinding and decision-making under uncertainty. Essentially, we have to teach these machines to not just see the water, but to truly understand it.

What is your forecast for underwater robotics?

My forecast is one of cautious but immense optimism. In the near future, I expect we’ll solve the power-to-weight problem for mid-sized robots, likely through clever hybrid actuation systems. This will unlock a whole new range of applications in marine biology, infrastructure inspection, and search and rescue. The bigger, long-term revolution will come from advances in AI and autonomous navigation. As these systems mature, we will transition from remotely operated vehicles to truly autonomous robotic explorers. Imagine deploying swarms of these ray-inspired robots that can intelligently coordinate to map the entire 74% of the unexplored seafloor, monitor the health of coral reefs, or search for new resources. They will become our eyes and hands in the deep, transforming our relationship with the ocean from one of mystery to one of understanding.