Oscar Vail is a pioneering expert at the intersection of robotics and bio-inspired design. His work involves looking to nature not just for inspiration, but for elegant, time-tested solutions to complex engineering problems. His latest project, the HERMES robot, is a testament to this philosophy, creating a hybrid machine that moves with the efficiency of a tumbleweed and the precision of a drone. This interview explores the journey from a chance observation on a windy day to the development of a robotic system poised to redefine exploration on Earth and beyond, delving into the specific aerodynamic principles, engineering challenges, and groundbreaking energy-saving strategies that make this technology so revolutionary.

The inspiration for HERMES struck while you were watching kite surfers and tumbleweeds. Can you walk me through that “aha” moment by Lake Neuchâtel and elaborate on the scientific puzzle presented by tumbleweeds, whose chaotic structure strangely generates more drag than a solid sphere?

Absolutely. That moment is still so vivid in my mind. It was a brisk, windy winter afternoon, and I was by the shores of Lake Neuchâtel. The air was filled with energy, and I was just captivated watching these kite surfers out on the water. They were masters of the wind, carving these beautiful, sweeping arcs, using its power not just to glide but to achieve these moments of effortless lift. It was a perfect display of harnessing natural forces. As I sat there, my mind started to wander, and I realized that nature has been perfecting this art for millions of years. My thoughts drifted from the high-tech kites to something far more ancient and humble: the tumbleweed. It’s this iconic image of the desert, a chaotic ball of twigs rolling across vast, empty landscapes, powered by nothing but the ambient wind. That’s when the puzzle really took hold. From a pure physics standpoint, a smooth, solid sphere should be the most aerodynamic shape, yet these messy, porous tumbleweeds somehow generate more drag. It was a fascinating contradiction, a piece of natural engineering that defied simple explanation. I knew right then that if we could unlock that secret, we could create a new class of robot that didn’t fight against its environment, but instead, danced with it.

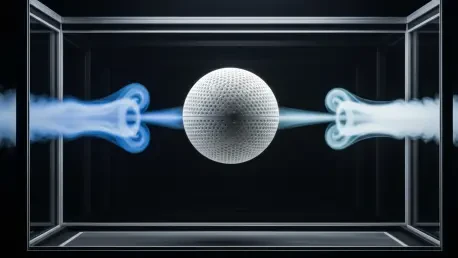

Your research identified a key vertical porosity gradient—60% on top and 40% on the bottom. Can you explain the step-by-step aerodynamic effect of this asymmetry? Specifically, how does it create 50% more drag and lead to the distinct somersaults and hops you observed?

Uncovering that porosity gradient was the real breakthrough. We started with a deep dive, using both computational fluid dynamics simulations and extensive wind tunnel experiments to map how air flowed around and through the tumbleweed’s structure. What we found was this incredibly subtle but powerful asymmetry. The upper half of the tumbleweed is more open, about 60% porous, while the bottom half is denser, only about 40% porous. This isn’t random; it’s a key design feature. When the tumbleweed sits upright in the wind, the air flows almost freely through the porous top half, but it gets blocked by the denser lower half, creating significant resistance and pressure drag. This difference is what generates the initial push to get it rolling. But the magic happens when it starts to move. As it tumbles and inverts, the denser region, now at the top, forces air to flow around it like a solid object. The newly positioned porous bottom half creates these complex, dual-lobed wake patterns behind it. This constant disruption and manipulation of airflow is what dramatically enhances the total drag. In our tests with winds at 12 m/s, this effect resulted in a staggering 50% more drag than a solid sphere of the same size. It’s this orientation-dependent force, a constant shifting of pressure and lift, that produces the tumbleweed’s signature movement—the gentle somersaults in low winds and the energetic hops and bounces it takes in stronger gusts.

Translating this to robotics, you had to balance structural strength, porosity, and internal space for a payload. Could you describe the engineering challenges in achieving this balance with selective laser sintering and how your computational modeling helped you outperform even natural tumbleweeds in your design?

That was precisely the core engineering challenge. It’s one thing to understand the principle, but it’s another thing entirely to build it. We were chasing a “Goldilocks” design. The structure had to be strong enough to survive rolling, tumbling, and impacting obstacles across rough terrain, yet it also had to be porous enough for the wind to grab it and generate that crucial drag. On top of all that, it needed to be roomy enough inside to house the quadcopter, sensors, and a payload. Making it too dense would make it strong but it wouldn’t roll; making it too porous would make it catch the wind but it would be too fragile. This is where modern fabrication and modeling became indispensable. We used selective laser sintering, a type of 3D printing, to build lightweight, intricate spherical shells with precisely engineered porosity gradients. But we couldn’t just print and test, it would have taken forever. The key was our custom computational modeling. It allowed us to run thousands of virtual simulations, tweaking the design parameters—the thickness of the struts, the size of the pores, the exact gradient—and seeing how each version would perform aerodynamically and structurally. This iterative process let us find the optimal balance much faster than physical prototyping ever could. In the end, our bio-inspired sphere was a fantastic success. It rolled effortlessly in winds as low as 1 m/s and actually generated substantially higher drag forces than the natural tumbleweeds that inspired it.

The hybrid system’s energy-aware philosophy is fascinating. Please detail the four operational modes and how brief 0.25-second motor pulses achieve 90-95% energy savings for course corrections, as shown in your maze tests where HERMES was both 48% more efficient and 37% faster.

The philosophy behind the hybrid system is beautifully simple: do not waste energy fighting the wind when you can sail with it. We designed the system to be fundamentally passive, only using power when absolutely necessary. This led us to develop four distinct operational modes. The primary mode is “tumbling,” where the robot is completely passive, letting the wind roll it across the terrain and expending zero energy. If it gets stuck against a rock or the wind dies down, it doesn’t just sit there. It enters a low-energy “spinning” or “gliding” mode. This involves a quick, targeted pulse from the internal motors—we’re talking bursts as short as 0.25 seconds—to nudge itself, reorienting it just enough to catch the wind again or to make a small course correction of 25 to 50 degrees. This is where we see those incredible 90 to 95% energy savings compared to continuous motor control. The final, and most energy-intensive, mode is “aerial,” where the internal quadcopter fully takes over to lift the robot and fly over an impassable obstacle. But flight is always the last resort. Our maze navigation tests really proved the concept. HERMES completed the course 37% faster than a robot using only active propulsion, and it did so while consuming 48% less energy. It’s faster because it’s smarter, using these tiny, efficient nudges to let the environment do the heavy lifting.

What is your forecast for the role of such bio-inspired, hybrid mobility systems in future planetary and terrestrial exploration?

I believe this approach signals a major paradigm shift. For decades, our model for exploration, especially on other planets, has been the single, highly complex, and meticulously planned rover. It’s effective, but it’s also slow, expensive, and limited in scope. I forecast that the future lies in decentralized swarms of smaller, more energy-efficient, and semi-autonomous robots like HERMES. Imagine deploying a hundred of these on Mars. Instead of a single rover following a pre-planned route, you’d have a fleet sailing across vast plains on the Martian winds, performing wide-area biomarker sweeps and making serendipitous discoveries we could never plan for. Back on Earth, they could drift over hazardous disaster zones to map radiation or float across vast minefields to flag dangers without risking a single human life. Of course, we still have hurdles to overcome—extending flight times beyond the current two-minute hover limit is a priority, as is developing adaptive shells that can tune their porosity on the fly. But the foundation is there. By integrating solar energy harvesting and advanced swarm coordination, these simple, resilient, and energy-aware systems will open up a new frontier of exploration, allowing us to cover more ground, gather more data, and do it more safely and sustainably than ever before.