A bombshell lawsuit filed in early 2026 has sent shockwaves through the digital privacy community, alleging that Meta possesses a secret capability to read the supposedly private messages of its two billion WhatsApp users. The claims, amplified by influential online personalities, paint a grim picture of compromised end-to-end encryption (E2EE), suggesting the platform’s core security promise is a facade. However, a meticulous analysis by Matthew Green, a respected cryptography expert from Johns Hopkins University, systematically dismantles these explosive allegations, highlighting a significant chasm between the lawsuit’s dramatic narrative and the technical realities of modern encryption. While the controversy reignites a crucial debate about trust in closed-source software, the expert consensus points not to a deliberate backdoor but to a fundamental misunderstanding of the technology at play. The ensuing discussion separates the unsubstantiated claims from the legitimate, albeit less sensational, privacy risks associated with the popular messaging application.

The Anatomy of an Accusation

The legal challenge at the heart of the controversy was initiated in a San Francisco federal court on January 26, 2026. The complaint makes the extraordinary claim that Meta has furnished its employees with internal tools that grant them unrestricted access to read private user communications on WhatsApp. Despite its viral spread, the lawsuit’s foundation appears remarkably thin from a technical standpoint. It offers no concrete evidence, such as code audits, network traffic analysis, or internal documentation, to substantiate its claims. Instead, the entire case hinges on assertions attributed to unnamed whistleblowers. In response, Meta issued a vehement denial, characterizing the accusations as “absurd” and a work of “headline-seeking fiction” designed to mislead the public. This has created a public-facing standoff between sensational, unverified allegations and a firm corporate rebuttal, leaving users caught in the middle and questioning the integrity of the platform’s security architecture without any verifiable data to guide their conclusions.

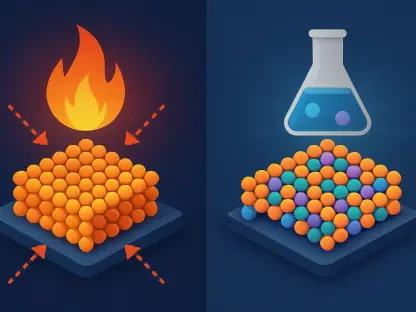

In a detailed technical rebuttal, Matthew Green explains that for the lawsuit’s claims to hold any water, Meta would have had to intentionally engineer a sophisticated backdoor into the WhatsApp application. The platform’s security is built upon the Signal protocol, a gold standard in cryptography that ensures encryption keys are generated and stored exclusively on the users’ devices. This design inherently prevents anyone other than the sender and receiver—including the platform provider—from accessing message content. Green argues that creating a mechanism to bypass this E2EE would be a monumental technical feat. Such a system would need to secretly exfiltrate either the plaintext messages before they are encrypted or the private keys themselves, all without being detected. An operation of this magnitude, deployed across billions of devices, would almost certainly leave discoverable forensic traces and be vulnerable to reverse engineering by the global security community. To date, no credible independent research has ever uncovered evidence of such a system within WhatsApp’s infrastructure.

Trust, Transparency, and Tangible Risks

This entire episode underscores a persistent and deep-seated tension in the digital privacy landscape: the conflict between corporate trust and verifiable transparency. WhatsApp, unlike open-source messaging platforms such as Signal, operates on a closed-source model. This means that its source code is not publicly available for independent security researchers and the general public to scrutinize and verify. Consequently, users are compelled to trust Meta’s public statements that the application functions exactly as advertised and that its implementation of the Signal protocol is secure and free from backdoors. For many privacy advocates, this reliance on trust alone is a deeply uncomfortable proposition, particularly given the tech industry’s track record with user data. The lack of independent verifiability creates a fertile ground for suspicion and allows claims, even those without strong evidence, to gain significant traction, as users have no definitive way to confirm the platform’s integrity for themselves.

While expert analysis concluded that the lawsuit’s central claim of a secret message-reading system was technically unsubstantiated, it also highlighted that legitimate privacy concerns regarding WhatsApp do exist. These concerns are distinct from the integrity of its core E2EE but are no less important. For instance, Meta has access to a significant amount of user metadata, which includes information about who users are communicating with, when, and for how long. Furthermore, the E2EE protections are rendered moot if users opt to create unencrypted cloud backups of their chat history on third-party services like Google Drive or iCloud, which can expose their messages to external access. Past research had also identified vulnerabilities, such as the “Prekey Pogo” flaw in 2025, that could potentially undermine certain privacy features without breaking the fundamental message encryption. The overarching takeaway from the expert analysis was that while users should remain vigilant with any closed-source software, the most sensational claims were unsupported. For individuals with paramount privacy needs, verifiable open-source alternatives remained the recommended path forward.