A revolutionary breakthrough in quantum computing thermal management has demonstrated a novel method where engineered noise, traditionally considered a primary source of computational error and decoherence, is harnessed as a powerful and efficient refrigeration tool. This development represents a fundamental paradigm shift in the approach to cooling quantum systems, transforming a destructive force into a constructive mechanism that challenges long-held assumptions. The core innovation lies in the ability to use precisely controlled noise patterns to actively extract heat from quantum processors, offering a more targeted and efficient alternative to conventional cooling technologies. By repurposing an element once viewed solely as a hindrance, this discovery has the potential to significantly accelerate the development timeline for scalable, practical quantum computers that can tackle problems far beyond the reach of today’s most powerful supercomputers.

The Persistent Challenge of Thermal Management

A significant and persistent bottleneck in the advancement of quantum computing is the extreme demand for thermal management. To preserve the fragile quantum states of qubits—the fundamental units of quantum information—processors must be cooled to temperatures approaching absolute zero, typically around 15 millikelvin. This requirement stems from the need to minimize thermal fluctuations, or “thermal noise,” which can randomly flip the state of a qubit, destroy its quantum superposition, and introduce errors into computations, a process known as decoherence. Even the slightest unwanted thermal energy can be enough to collapse a complex quantum calculation, rendering the entire operation useless. The quest for quantum supremacy is, in many ways, a battle against heat. The stability and reliability of any quantum computer are directly tied to how effectively it can be isolated from the thermal chaos of the surrounding environment, making cooling one of the most critical and resource-intensive aspects of the entire field.

Currently, the industry standard for achieving these ultra-low temperatures relies on dilution refrigerators, massive, complex, and costly pieces of infrastructure that use a mixture of helium-3 and helium-4 isotopes to create a continuous cooling cycle. The operational and capital costs associated with these systems are substantial; a single top-tier dilution refrigerator can cost upwards of $500,000, consume as much electrical power as a small data center, and require constant, specialized maintenance. This immense overhead presents a major barrier to scaling quantum computers from today’s small-scale prototypes with hundreds of qubits to the millions of stable qubits required for solving real-world, high-impact problems. The energy consumption, physical footprint, and financial investment required by conventional cooling methods are simply unsustainable for the future vision of large-scale quantum data centers, pushing researchers to find more elegant and efficient solutions.

A Counterintuitive Solution from Quantum Physics

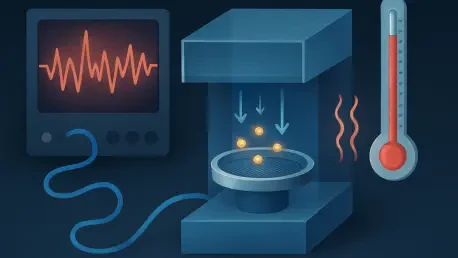

The newly discovered technique fundamentally reimagines the role of noise in quantum mechanics by demonstrating that it can be engineered to perform targeted work on a quantum system instead of being an indiscriminate source of disruption. The mechanism is rooted in a quantum phenomenon known as “stochastic thermalization,” where carefully structured random fluctuations in electromagnetic fields are used to selectively remove energy from specific quantum states. The research team accomplished this by designing and generating noise signals with precisely controlled spectral properties—that is, specific frequencies, amplitudes, and phases. When these engineered noise patterns are introduced to the quantum processor, they are tuned to preferentially couple with the higher-energy states of the qubits. This interaction effectively excites the qubits in a way that encourages them to shed thermal energy, creating a microscopic thermal gradient that actively draws heat away from the quantum chip, functioning as a quantum-level refrigeration cycle.

This discovery builds upon the theoretical foundations of quantum thermodynamics, a field that explores how the principles of heat and energy flow operate at the quantum scale. Unlike in classical thermodynamics, where adding random energy (noise) to a system invariably increases its temperature, quantum thermodynamics allows for counterintuitive behaviors. The structured noise creates conditions akin to “negative temperature” states, where the normal direction of energy flow is reversed, enabling heat to be extracted from a cold object (the qubit) into a controlled environment (the noise field). This principle is conceptually similar to laser cooling, a well-established technique for cooling atoms, but has now been adapted for the much more complex environment of a solid-state quantum processor. This represents a pivotal moment where a deep understanding of quantum mechanics has been leveraged to turn one of the field’s greatest adversaries into an invaluable ally in the quest for computational power.

From Theory to Practical Implementation

Translating this theoretical breakthrough into a practical and scalable technology presents considerable engineering hurdles that must be overcome. The success of noise-based cooling is entirely dependent on the extraordinary precision with which the noise signals are generated and controlled. The generation of the noise itself requires specialized microwave equipment capable of producing complex noise patterns with sub-hertz frequency resolution and amplitude control sensitive enough to operate at the single-photon level. Even minuscule deviations from the optimal noise profile can completely reverse the intended effect, causing the noise to heat the quantum processor instead of cooling it, which would be catastrophic for the computation. This places extreme demands on the hardware used to generate and deliver the noise, requiring a level of control and stability that pushes the boundaries of current microwave engineering.

A sophisticated, real-time feedback and control system is essential for any practical implementation of this technology. This system must continuously monitor the temperature of the quantum processor and adjust the noise characteristics on the fly to maintain optimal cooling. This requires the use of quantum-limited thermometry—highly sensitive measurement techniques that can extract temperature information without significantly disturbing the delicate quantum states of the qubits themselves. The entire closed-loop control architecture must operate at microsecond timescales, making it fast enough to react to and suppress thermal fluctuations before they can induce decoherence. Despite these challenges, early laboratory experiments have yielded highly promising results. In one demonstration, researchers successfully used engineered noise to cool a superconducting qubit array from 25 millikelvin down to 17 millikelvin, a 30% reduction that led to a direct improvement in quantum performance by extending the coherence time of the qubits by nearly 40%.

The Path Forward to Commercial Viability

The quantum computing industry, which includes major players like IBM, Google, and IonQ, recognizes that thermal management is a primary obstacle to scaling, making the prospect of noise-based cooling a subject of significant interest. The most likely near-term application is a hybrid cooling architecture where conventional dilution refrigerators perform the initial “brute-force” cooling while engineered noise provides targeted, supplemental cooling for the most critical components. Preliminary industry analyses suggest that such a hybrid approach could reduce the overall power requirements for cooling by 20-30%. For future quantum data centers planning to operate thousands of quantum processors, this level of efficiency gain would translate into tens of millions of dollars in annual energy savings and a significantly reduced environmental footprint. This technology could also unlock new avenues for quantum processor design, enabling the use of advanced qubit architectures that require even lower operating temperatures than current systems can reliably achieve.

The implications of this discovery extend beyond quantum computing, as other quantum technologies that rely on ultra-low temperatures stand to benefit. Quantum sensors, which are used for high-precision measurements of magnetic fields, gravity, and time, could be made more sensitive, compact, and portable, opening up applications in medical imaging and mineral exploration where precision is paramount. Furthermore, quantum communication networks, which use single-photon detectors and quantum memory that operate more effectively at cryogenic temperatures, could also leverage this technology to reduce the infrastructure requirements at each network node. This would not only lower the cost but also accelerate the deployment of quantum-secure communication systems, bringing the promise of unhackable communication closer to reality for government, finance, and other critical sectors.

Overcoming the Final Hurdles

While the proof-of-concept demonstrations were a resounding success, the path to commercial implementation required overcoming substantial scaling challenges. Current systems had only been tested on small arrays of fewer than 20 qubits. Extending the technique to processors with thousands or millions of qubits necessitated solving complex problems related to noise distribution, managing thermal gradients across a large chip, and mitigating electromagnetic interference and crosstalk between signals. One major hurdle was maintaining the phase coherence of the noise signals as they propagated across a large-scale processor, a task that demanded new engineering solutions for signal integrity at the quantum level. The physics that worked perfectly on a handful of qubits needed to be re-validated and re-engineered for the massive parallelism that defines useful quantum computers.

Another critical consideration was the interplay between this “beneficial” noise and quantum error correction (QEC) protocols. QEC is essential for reliable quantum computation, and its algorithms were designed under the assumption that all noise is destructive and must be corrected. Integrating a cooling system that relied on intentionally introduced noise required a fundamental rethinking of QEC algorithms, enabling them to distinguish between harmful noise that corrupted data and beneficial noise that provided a thermal advantage. Finally, the transition from laboratory to industry necessitated a move from manual to automated systems. For commercial viability, automated calibration systems had to be developed to configure and maintain optimal cooling performance without human intervention, ensuring the long-term stability and reliability required for quantum computers to operate continuously for days or weeks at a time.