We are joined today by Oscar Vail, a technology expert at the forefront of advancements in robotics and artificial intelligence. As humanoid robots step out of research labs and into the public eye, they bring with them a storm of excitement, apprehension, and complex questions. We’ll be exploring the delicate balance between lifelike design and practical function, the engineering marvels and missteps in achieving human-like movement, and the real-world applications for these increasingly sophisticated machines. Our conversation will delve into why a robot with warm skin might be more than a novelty and how public trust is shaped by both flawless performance and spectacular failures.

Moya is being called the first “biomimetic AI robot” with unique features like warm skin. How does this design philosophy differ from competitors, and what specific engineering hurdles must be cleared to bridge the uncanny valley? Please share some technical details on achieving this.

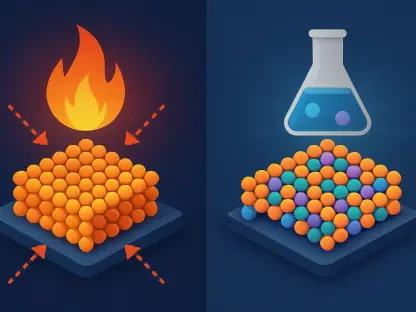

The term “biomimetic” is key here, and it represents a fascinating philosophical split in the industry. While many competitors are laser-focused on perfecting the mechanics of movement, Droidup is betting on sensory details to create a connection. The idea of a robot having warm skin, maintained between 32 and 36 degrees Celsius, is a direct attempt to mimic a fundamental aspect of life that we process subconsciously. It’s a departure from the cold, metallic feel we associate with machines. However, this is also where the uncanny valley becomes a treacherous path. The moment you introduce a lifelike quality like warmth, any unnatural element—like the “plasticky skin” or “dead eyes” observers noted—becomes jarringly amplified. The engineering challenge is immense; it’s not just about installing a heating element. You need a sophisticated thermal regulation system that dissipates heat from the internal electronics in a way that feels organic, without creating hot spots or compromising the delicate sensors and motors. This is a monumental task that goes far beyond just programming a walking gait.

Moya’s walking style is rated at 92% accuracy, yet observers describe it as a “gingerly shuffle.” Could you break down how this accuracy metric is calculated? Please walk us through the key innovations in its ‘Walker 3’ skeleton that differentiate it from previous-generation bipedal robots.

That 92% accuracy figure is a classic example of how internal engineering metrics don’t always align with human perception. The number likely refers to the robot’s ability to replicate a pre-programmed path or maintain balance under specific conditions with minimal deviation. It’s a measure of precision, not naturalness. So, while Moya may be hitting its programmed footsteps with 92% fidelity, our eyes perceive the result as a “gingerly shuffle” because it lacks the subtle, dynamic weight shifts and fluidity of human locomotion. The innovation in the ‘Walker 3’ skeleton is clearly about stability and endurance. We know its predecessor won a bronze medal in a robot half-marathon, which tells us the underlying hardware is robust and capable of sustained operation. The key differentiation from older bipedal robots is likely a combination of more advanced actuators for finer motor control and superior balance-correcting algorithms. However, as we can see, translating that mechanical success into a graceful, convincing walk is an entirely different, and arguably harder, challenge.

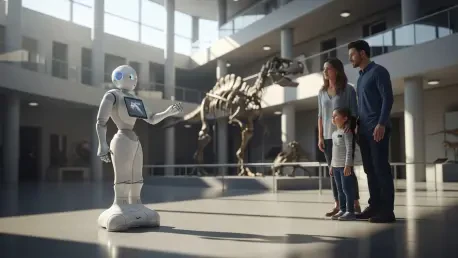

With a projected price of around $173,000, Moya is aimed at public service roles in banks and museums, not homes. What specific tasks justify this high cost over human employees or simpler tech? Can you provide a step-by-step example of how Moya would handle a complex public interaction?

At that price point, you’re not buying a simple replacement for a kiosk or a human greeter; you’re investing in a platform. The justification for the $173,000 cost lies in its potential for continuous, multilingual, and data-driven service. A human employee works in shifts, but a robot like Moya can operate almost continuously. Imagine a scenario in a large, busy museum. A family approaches Moya. First, the camera behind its eyes uses facial recognition to gauge the general age of the group and perhaps their emotional state. The parents ask for directions to the dinosaur exhibit while also wanting to know where the nearest restroom is. The robot’s AI processes both requests simultaneously, plots the most efficient route on a digital map displayed on a nearby screen, and verbally explains the directions. As it speaks, it uses “micro expressions” to appear more engaging. While doing this, it could also be scanning for security risks or alerting maintenance to a nearby spill it detected, tasks a human might miss while focused on the conversation. It’s this multi-tasking and integration with the building’s digital infrastructure that vendors believe will eventually justify the high initial investment.

Public reactions to lifelike robots have been mixed, with some finding them unsettling. Meanwhile, competitors aim for hyper-realistic movement. How critical is aesthetic design versus raw functionality in gaining public trust, and what key lessons has the industry learned from public demo mishaps?

This is the central tension in humanoid robotics today. The industry has learned a very public and sometimes painful lesson: trust is fragile. Aesthetic design is a double-edged sword. A friendly, less-humanoid appearance can be more readily accepted, while a hyper-realistic robot that moves imperfectly, like Moya, can trigger a strong “uncanny valley” rejection. Comments like “it walks like a ghost” are incredibly telling. Conversely, raw functionality can win people over, but only if it’s flawless. The spectacular face-plant of Xpeng’s IRON during its demo became a viral moment. While embarrassing for the company, it also, paradoxically, made the robot seem less threatening. These public fails have become a rite of passage, teaching designers that over-promising on realism is dangerous. The key lesson is that managing expectations is paramount. It’s better to deploy a robot that looks like a machine but performs its task perfectly than one that looks human but moves in a way that feels deeply unsettling or fails spectacularly.

What is your forecast for humanoid robots?

My forecast is that we will see a significant divergence between two distinct types of humanoid robots over the next decade. The first type will be the “public-facing” robot, like Moya, designed for interaction in places like museums and banks. Their development will focus heavily on improving aesthetics, communication, and navigating the uncanny valley to gain public acceptance. The second, and I believe more impactful, type will be the “industrial” humanoid. These robots won’t need warm skin or a friendly face. They will be purely functional machines designed for warehouses, manufacturing, and logistics, where bipedal, human-like form is advantageous for navigating spaces built for people. They will become the true workhorses, while their more lifelike cousins serve as the ambassadors, slowly acclimating society to the idea of intelligent machines walking among us. The real revolution won’t be in our homes, but behind the scenes in the engines of our economy.