The deterministic blueprints that built the industrial age are proving increasingly fragile in a world defined by interconnected chaos and profound uncertainty. For centuries, the discipline of design has operated under the influence of a Newtonian worldview—a reality of discrete objects, linear causality, and predictable systems that are merely the sum of their parts. This mechanistic model, while historically effective, is now fundamentally ill-equipped to address the complex, non-linear “wicked problems” of our time, from climate change to systemic inequality. Into this void steps an unlikely but powerful new paradigm, drawn from the strange and counterintuitive principles of quantum mechanics. This convergence is not a superficial intellectual exercise but a necessary evolution, offering a profound epistemological and ontological foundation to radically reimagine design theory and practice. The core concepts of quantum mechanics—superposition, entanglement, and the observer effect—provide a revolutionary framework for designing not for fixed outcomes, but for emergent possibilities within a deeply relational world. This transformation is unfolding on two critical fronts: the conceptual level, where quantum philosophy reframes the very act of thinking about design, and the material level, where its physical laws enable the engineering of reality at the atomic scale.

The Allure and Peril of Quantum Language

The initial entry of quantum mechanics into design discourse has been predominantly through the evocative power of metaphor, offering a sophisticated lexicon to articulate the complexities of modern life. Concepts like “superposition” and “entanglement” resonate deeply with contemporary challenges. A digital user interface, for instance, can be conceived as existing in a state of superposition, holding a multitude of potential interaction pathways that only “collapse” into a single, definite experience upon user engagement—a form of measurement. Similarly, the intricate web of a global product supply chain mirrors the principle of entanglement, where a single disruption in a remote factory can have instantaneous, non-local consequences on retailers and consumers across the globe, defying simple, linear models of cause and effect. This metaphorical framework presents a compelling shift in the designer’s role, moving from a deterministic author of a final product to a cultivator of possibilities. In this view, the designer creates “probability fields” of potential futures and experiences rather than rigid, predetermined outcomes, embracing uncertainty as an inherent quality of the system. This approach promises a more fluid, adaptive, and responsive mode of design, seemingly better suited to the unpredictable nature of the 21st century.

However, the uncritical appropriation of this scientific language carries significant risks, chief among them the descent into a “shallow quantum mysticism.” When complex, mathematically precise terms are co-opted as inspirational but hollow slogans, they are stripped of their original rigor and can lead to conceptual confusion and pseudo-scientific claims. In quantum mechanics, uncertainty is not a vague notion of unpredictability; it is a precisely defined and quantifiable concept. The Schrödinger equation deterministically describes the evolution of a system’s wave function, with the probability of a specific outcome given by the square of its amplitude. This mathematically grounded understanding of probability is vastly different from the colloquial use of “uncertainty” to describe the stochasticity of user behavior or market trends. For a quantum metaphor to be genuinely transformative, it must move beyond vocabulary appropriation and engage with the deeper philosophical implications of the theory. This requires a rigorous examination of concepts like the dissolution of the subject-object duality, a core tenet of quantum thought that directly challenges the traditional view of the designer as an objective, external observer. Without this critical depth, the language of quantum physics becomes mere ornamentation rather than a tool for profound change.

The Material Revolution at the Nanoscale

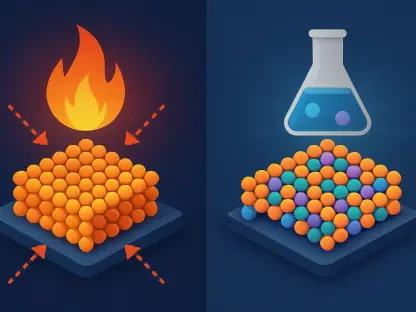

Transitioning from the conceptual to the concrete, the most tangible and quantitatively verifiable intersection of design and quantum mechanics lies in material science. Here, quantum theory is not an analogy but a predictive and foundational guide for engineering physical reality. The constraints of classical physics dissolve at the nanoscale, giving way to a realm where designers can directly manipulate the fundamental properties of matter by harnessing quantum effects. This represents a paradigm shift from designing with existing materials to designing the materials themselves, atom by atom. The primary example of this revolution is the quantum dot (QD), a semiconductor nanocrystal typically just 2-10 nanometers in size. At this minuscule scale, materials exhibit bizarre and powerful properties not present in their bulk form due to an effect known as “quantum confinement.” In a bulk semiconductor, electrons have the freedom to move, and the energy required to excite them is fixed. In a quantum dot, however, the physical confinement of these electrons quantizes their energy levels, making their behavior dependent on the size of the crystal. This principle transforms matter from a passive substance into an active medium for design innovation.

This quantum-level control becomes a practical design tool through principles like the Brus equation, which demonstrates that the optical properties of a quantum dot are a direct, deterministic function of its physical size. By precisely controlling the radius of the nanocrystal, a designer can tune the color of light it emits when excited. Smaller dots emit higher-energy, blue light, while larger dots emit lower-energy, red light, with a continuous spectrum of possibilities in between. This transforms a fundamental quantum principle into a precise engineering rule, granting designers a level of control over light and color that was previously unimaginable. This mastery has already fueled significant technological and economic progress. The quantum dot market, which achieved a valuation of USD 10.6 billion recently, is projected to grow with a compound annual rate of 21.5% from 2025 to 2031, driven by applications in display technology. QLED screens, powered by these nanocrystals, offer a wider color gamut, superior brightness, and greater energy efficiency than their predecessors. Beyond consumer electronics, QDs are revolutionizing biomedical imaging, where they can be functionalized to bind to specific cancer cells, providing high-contrast, multiplexed visualization for diagnostics and therapy, and they promise to dramatically increase the efficiency of solar cells by allowing them to capture a broader range of the solar spectrum.

Dismantling Objectivity in Design Practice

Perhaps the most radical implications of quantum theory are those that challenge the foundational axioms of mainstream design, particularly the dominant paradigm of Human-Centered Design (HCD). At the heart of this challenge is the “observer effect,” a cornerstone of quantum mechanics which posits that the act of observation is not passive; it fundamentally affects the system being observed, collapsing its potential states into a single, realized outcome. This principle dismantles the classical Newtonian ideal of an objective, independent reality that can be observed without disturbance. When applied directly to design research, this has profound consequences. Traditional HCD methods, such as user interviews and ethnographic observation, are largely framed under the Newtonian assumption that they can “uncover” pre-existing, objective user needs as if they were geological artifacts waiting to be unearthed. The quantum perspective refutes this entirely, arguing instead that the designer-researcher is an entangled participant in the process. The research itself—the questions asked, the context created, the methods employed—co-creates the reality it purports to observe by collapsing the user’s vast field of potential behaviors into the specific ones elicited by the study.

This recognition demands a fundamental shift in the goal of design research. The objective moves from discovering objective truths to facilitating a co-creative process where the designer and user collaboratively construct a shared reality. It provides a deep philosophical grounding for participatory design methods that have long been practiced but often lacked a robust theoretical underpinning. The designer is no longer a detached expert diagnosing a problem from the outside but an integral part of the system being designed, entangled with the subjects and objects of their work. This perspective compels a new form of humility and responsibility, acknowledging that design interventions do not simply solve problems within a system but actively reconfigure the system itself. It forces designers to confront their own influence and biases not as contaminants to be eliminated but as active forces in the creation of new realities. Embracing this entanglement means moving away from a posture of objective authority and toward one of collaborative inquiry, where the design process becomes a shared exploration of what could be, rather than a unilateral imposition of what should be.

Designing for Interconnected and Potential Futures

The quantum principle of entanglement, which describes a state where multiple particles are linked in such a way that their individual states cannot be described independently of the others, offers a powerful lens for understanding and practicing systemic design. This concept of “non-locality” directly contradicts the reductionist impulse to break complex problems down into smaller, manageable parts. Applied to design, entanglement argues against the practice of creating discrete, isolated products. Every designed object or service, from a simple chair to a complex software platform, exists within an intricate and entangled web of social, economic, environmental, and political systems. A conventional design approach might focus on a “local” improvement, such as the ergonomics of the chair or the user interface of the software. A quantum-inspired practice, however, demands consideration of the entire entangled system. The design of a smartphone, for example, is inextricably entangled with Congolese mineral extraction, Chinese factory labor conditions, Silicon Valley software ecosystems, and global patterns of social media consumption and their effects on mental health. Designing with an awareness of this entanglement requires a shift in focus from the object itself to the health and well-being of the whole network.

This systemic view is further enriched by the principle of superposition, where a system can exist in multiple potential states simultaneously until it is measured. For designers, this provides a powerful model for speculative design and future-thinking. Rather than designing for a single, predetermined future, designers can create artifacts and scenarios that embody multiple “superimposed” futures. These designs act as “probes” that bring these latent possibilities into the tangible present, allowing society to engage with them, debate them, and essentially “measure” them through interaction and discourse. This public engagement effectively “collapses the wavefunction” of possible futures, guiding collective movement toward a more intentionally chosen and collectively desired outcome. This approach transforms design from a problem-solving activity focused on the present into a future-making practice. It aligns with the strategic work of speculative designers who use design to pose “what if?” questions, opening up public discourse about the kinds of futures we want to create and inhabit, and giving us tools to navigate the profound uncertainty of our time not with fear, but with intention and imagination.

A Necessary Leap Into a Quantum Mindset

The dialogue between quantum mechanics and design was ultimately revealed to be an evolutionary imperative for the discipline. The analysis showed a convergence on two fundamental levels. In the material realm, quantum mechanics provided a quantitative and predictive foundation for a new era of material innovation, enabling the engineering of reality at the atomic scale with unprecedented precision. The economic and technological impact of technologies like quantum dots represented just the beginning of a revolution that was poised to redefine the designer’s material palette. At the theoretical and philosophical level, quantum principles offered a potent conceptual toolkit to dismantle the outdated Newtonian legacy in design thinking. The observer effect compelled a necessary shift from the illusion of objectivity to an embrace of our entanglement with the subjects and objects of our work. The concepts of non-locality and entanglement demanded a move from designing isolated products to designing for complex, interconnected systems, while superposition provided a framework for embracing uncertainty and exploring a plurality of possible futures. The most critical task identified was the need to guide this convergence with intellectual rigor and critical discipline, avoiding the trap of shallow metaphor. By doing so, design had the potential to transform from a discipline that creates in the world to one that co-creates with the world, skillfully navigating and shaping the deeply interwoven, probabilistic, and relational fabric of reality.